FIELDWORK

Partition

[Cyprus Pt. I]

2021

“When anyone sees the division for the first time, from whichever side of Nicosia, it makes a very strong impact. The physical shape and appearance of the two sides of the border differ remarkably, but everywhere it has an exceptional character. To begin with, its position in the heart of the town creates an impression of loss and of something that once profoundly marked the historical heritage and the urban landscape. Tourists and newcomers are astonished when they realise the state of desolation and decay not only of the buffer zone but of the nearby neighbourhoods. This surprising landscape not only makes a strong visual impact on visitors and passers-by: it also allows interpretations concerning how the political and historical discourse takes shape in space.”

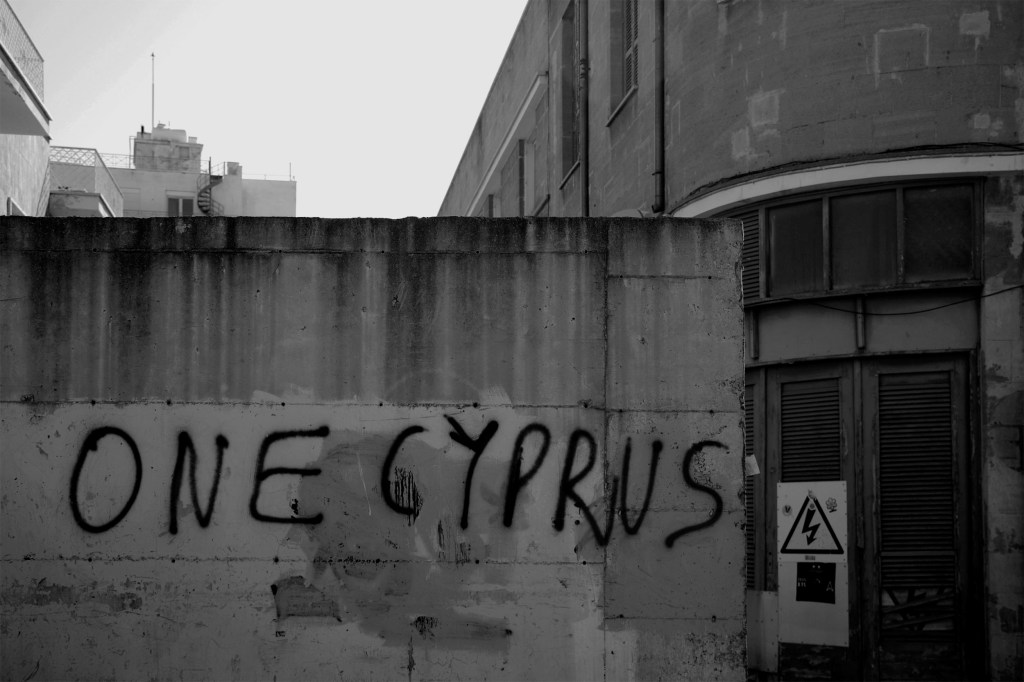

“The physical appearance of the division is closely tied to the different meanings it has for the two sides. The same definition of the line as a “border” is also contested by its appearance.The physical appearance of the border differs remarkably on the two sides, and it gives many clues to understanding the different meanings given to it by the conflicting communities. On the Greek side barbed wire, sand bags, and barrels mark the division; there has been no attempt to change this since 1974. On the Turkish side the border is marked by a wall, which was built after the proclamation of the TRNC. These very different physical characteristics ‘mirror the two sides’ political views and objectives’ (Hocknell et al., 1998, 156). […] The temporary nature of the border on the southern side reveals the non-acceptance of the division and underlines the state of exception due to the military occupation, besides reiterating the will to reunify the island, while the construction of a wall on the northern side shows the attempt to give it the meaning of an official and stable border.”

“The analysis of the urban landscape as a political landscape considers concrete objects in space (dell’Agnese, 2004): the aim is to understand these artefacts as social products related to certain ideas and ideologies. Through this approach it is possible to identify the specific symbolic meaning of every element, relating it to the others and the landscape as a whole. Moreover, we can interpret ideas and ideologies ascribed to the materiality of the city as the product of a discourse, and the landscape itself as the result of a discursive practice (ibid., 261). However, the meaning we attribute to a given landscape cannot be the only true one, because there is no single way to read it, and the landscape is always undergoing transformation. Moreover, meanings are not only modified because of spatial reconfigurations but as a result of different “ways of seeing”: culture, politics and subjectivity continuously interconnect, configuring and reconfiguring the urban landscape, not only as a material artefact but also as a way of seeing (ibid., 261). These last considerations introduce a reflection on the positionality of the researcher and the partial character of any interpretation, which is unavoidable especially when dealing with the critical analysis of discourses and narratives.”

“Notwithstanding its closure the buffer zone is visible: from the southern side it is easy to see inside, given the configuration of the border and the possibility to access part of the no man’s land; from the north, the deterioration of buildings is still visible despite the wall, because many structures in the buffer zone are taller than it.

Its presence is the materialisation of the city’s wound, an open-air memorial to the conflict, whose power lies precisely in its slow disintegration, the inevitable effect of time on an inaccessible area. It symbolises the relations of conflict fixed in space-time, a reminder of the war, a mirror of the occupation. The feelings it provokes to the inhabitants of Nicosia are generally very strong, either in memories for those who were there during the war or with regard to the present political situation. […] citizens have a very peculiar relationship with the space of the buffer zone and the surrounding area, a mixture of attraction and repulsion because of the intensity of its experience. Indeed, personal stories and memories influence this attitude, but the very configuration of the buffer zone cannot but enforce it.”

Excerpts from: Casaglia, A. (2020). Nicosia Beyond Partition. Complex Geographies of the Divided City. Milan: Unicopli [pp. 57, 148-150, 157]